Introducing Winbindex - the Windows Binaries Index

I indexed all Windows files which appear in Windows update packages, and created a website which allows to quickly view information about the files and download some of them from Microsoft servers. The files that can be downloaded are executable files (currently exe, dll and sys files). Read on for further information.

Motivation

During a recent research project, I had to track down a bug that Microsoft fixed in one of the drivers. I needed to find out which update fixed the bug. I knew that the bug exists on an unpatched RTM build, and is fixed on a fully patched system. All I needed was the dozens of file versions of that driver, so that I could look at them manually until I find the version that introduced the fix. Unfortunately, to the best of my knowledge there was no place where one could get just these dozens of files without downloading extra GBs of data, be it ISOs or update packages. While searching for the simplest solution, these are the options I considered:

- Install an unpatched RTM build with automatic updates disabled, and install each update manually. Get the driver file after each installed update. A more efficient option would be to do a binary search, installing the middle update first, and then continuing with the relevant half of the updates depending on whether that update fixed the bug.

- Extract each version of the file from a Windows package, such as an update package that can be download from the Microsoft Update Catalog or an archive from the Unified Update Platform.

- Look for the driver files on the internet. There are various fishy “dll fixer” websites that claim to provide versions of system files. Unfortunately, not only that these websites are mostly loaded with ads and the files are sometimes wrapped with a suspicious exe, they also don’t provide any variety of versions for a given file, usually having only one, seemingly randomly selected version. There are also potentially useful services like VirusTotal, but I didn’t find any such service which allows to freely download the files.

Option 3 didn’t work, and I chose option 2 over 1 since downloading and extracting update packages seemed quicker than updating the OS every time. I also chose the Microsoft Update Catalog over the Unified Update Platform, since the latter is not really documented and is more obscure, and other than that provides no obvious benefits. Also, the update history is nicely documented by Microsoft: Windows 10 update history. There’s also Windows 7 SP1 update history and Windows 8.1 update history, but I focused on Windows 10.

What’s in an update package

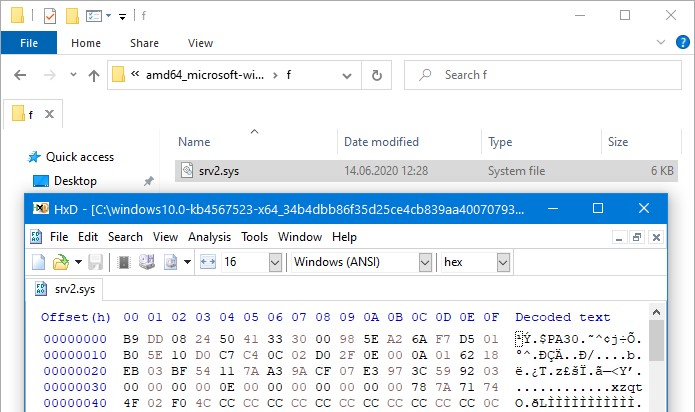

Each update package that can be downloaded from the Microsoft Update Catalog is an msu file, which is basically a cab archive. Extracting it results in some metadata and another cab archive, which in turn contains the Windows files of the update. The update files are divided to assemblies, each assembly having a manifest file and a folder with the actual files. I expected that it would be enough to grab the file I’m looking for from the corresponding folder, but it turns out that newer update packages contain forward and reverse differentials instead of the actual files.

Only 6 KB, no MZ header, clearly not the file I’m looking for.

A quick search about the diff patching algorithm didn’t yield results, and I’d need the base Windows version anyway, so this option didn’t look appealing anymore. Just before giving up and trying the other options (the Unified Update Platform and installing updates manually), I looked at the information that is available in the manifest file. The only potentially interesting piece of information that I found is the list of files, which, among various unhelpful (for me) information, contains the file’s SHA256 hash:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" standalone="yes"?>

<assembly xmlns="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:asm.v3" manifestVersion="1.0" copyright="Copyright (c) Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved.">

<assemblyIdentity name="Microsoft-Windows-SMBServer-v2" version="10.0.19041.153" processorArchitecture="amd64" language="neutral" buildType="release" publicKeyToken="31bf3856ad364e35" versionScope="nonSxS" />

<dependency discoverable="no" resourceType="Resources">

<!-- ... -->

</dependency>

<file name="srv2.sys" destinationPath="$(runtime.drivers)\" sourceName="srv2.sys" importPath="$(build.nttree)\" sourcePath=".\">

<securityDescriptor name="WRP_FILE_DEFAULT_SDDL" />

<asmv2:hash xmlns:asmv2="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:asm.v2" xmlns:dsig="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

<dsig:Transforms>

<dsig:Transform Algorithm="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:HashTransforms.Identity" />

</dsig:Transforms>

<dsig:DigestMethod Algorithm="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#sha256" />

<dsig:DigestValue>pD5a0dKSCg7Kc0g1yDyWEX8n8ogPj/niCIy4yUR7WvQ=</dsig:DigestValue>

</asmv2:hash>

</file>

<memberships>

<!-- ... -->

</memberships>

<instrumentation xmlns:ut="http://manifests.microsoft.com/win/2004/08/windows/networkevents" xmlns:win="http://manifests.microsoft.com/win/2004/08/windows/events" xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema">

<!-- ... -->

</instrumentation>

<localization>

<!-- ... -->

</localization>

<trustInfo>

<!-- ... -->

</trustInfo>

</assembly>You can see it under DigestValue, encoded as base64. In this case, that’s pD5a0dKSCg7Kc0g1yDyWEX8n8ogPj/niCIy4yUR7WvQ= which translates to a43e5ad1d2920a0eca734835c83c96117f27f2880f8ff9e2088cb8c9447b5af4. Can a SHA256 hash help me get the file? Maybe…

The Microsoft Symbol Server

Having some experience with the Microsoft Symbol Server, I know that it doesn’t only store symbol files, but also the PE (Portable Executable) files themselves. You can refer to the great article Symbols the Microsoft Way by Bruce Dawson for more details, but the most important detail for us is that the format for the path to each PE file in a symbol server is:

“%s\%s\%08X%x\%s” % (serverName, peName, timeStamp, imageSize, peName)

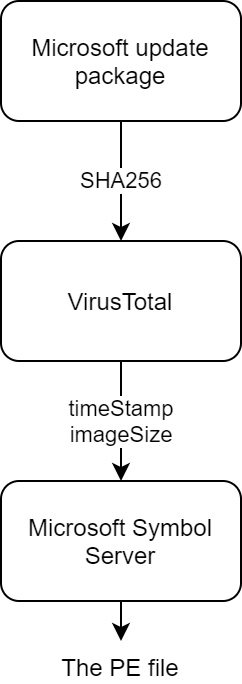

This means that all we need to retrieve the file from the Microsoft Symbol Server is to know the file’s timestamp and image size. But at this point, we only have the file’s SHA256 hash.

VirusTotal to the rescue

VirusTotal is a well known service for scanning files and URLs with multiple antivirus products and online scan engines. In addition to the scan results, VirusTotal displays some information about the submitted files. For PE files, it displays information such as imports and resources, but more importantly, it also displays the files’ timestamp and a list of sections. The latter can be used to calculate the file’s image size.

In addition, if the file was scanned with VirusTotal before, the information can be retrieved by providing the file hash. That means that for each file previously scanned by VirusTotal, the SHA256 hash is enough to deduce the correct path on the Microsoft Symbol Server and download the file.

Back to our example, the a43e5ad1d2920a0eca734835c83c96117f27f2880f8ff9e2088cb8c9447b5af4 hash can be found on VirusTotal, and the parameters that we need are the creation time:

Creation Time: 2096-10-28 20:47:11

And the last section in the list of sections:

Name: .reloc

Virtual Address: 798720

Virtual Size: 12708

…

You can Google for an “epoch converter” to convert the creation time to an epoch timestamp: 4002295631, or in hex: 0xee8e2f4f. You might need to append “GMT” to prevent the converter from reading the creation time as a local time.

To calculate the image size, just add the virtual address and size of the last section: 798720+12708 = 811428 = 0xc61a4, and then align to the size of a page, which is 0x1000: 0xc7000.

Combining the above, we can now build our download link: https://msdl.microsoft.com/download/symbols/srv2.sys/EE8E2F4Fc7000/srv2.sys

Here’s a simple Python script which generates a Microsoft Symbol Server link from a file name and a file hash, automating what we just did manually.

P.S. In case you’re wondering how come the file was created in 2096, it wasn’t. Starting with Windows 10, the timestamps of the system’s PE files are actually file hashes, a change that was made to allow reproducible builds. For more details see Raymond Chen’s blog post, Why are the module timestamps in Windows 10 so nonsensical?.

P.P.S. If you read Bruce Dawson’s article, you saw that he talked about possible collisions in case there are two different files with the same timestamp and image size. He also described how Chrome had this exact problem. But Chrome used real timestamps, what about the pseudo-timestamps which are in fact file hashes that Windows 10 is using? In Windows’ case there are many collisions. I stumbled upon one, and got curious about the actual amount of such collisions, so I wrote a script to find all of them. Here’s the result, 3408 collisions!

For most collisions (all but 54) the only different section is .rsrc which contains resource information, which means that the code and the data are the same. Perhaps the hashing algorithm isn’t affected by that section. I took one specific example (aitstatic.exe) and compared my system’s file (in a collision list) with the file served by the symbol server. The two had a different file version, the file served by the symbol server wasn’t signed, and the checksum (the real checksum field in the PE header, not the timestamp-checksum) was different. Also the file that was served by the symbol server was different than all of the files that I found in update packages. Looks like the symbol server sometimes returns a development file instead of a production one, which might be unsigned and have a different version. It might be confusing, and I’ve been bitten by this once, so remember: never trust the version of a file you download from the Microsoft Symbol Server.

The other 54 collisions are of .NET PE files, and in this case other sections are different as well. But that doesn’t really matter, since they’re not available via the symbol server at all.

Building an index

That’s how I solved my problem, downloading several update packages and getting the driver files with the help of VirusTotal. But since all the files are so conveniently available via the Microsoft Symbol Server, I thought that it would be nice to index all of the files once, making the links for all PE files and versions available and saving myself and others from having to go through the procedure in the future. All I had to do is to get the list of updates from the Windows 10 update history page (for now, I looked only at Windows 10 updates), download these updates from the Microsoft Update Catalog, fetch the file names and hashes, query VirusTotal for these hashes, and make some nice interface to search in this index and generate links.

Getting the list of updates

That was the easy part, a simple Python script did the job. A funny thing I noticed is that the help page titles are edited manually, since they’re almost uniform, but some of them contain minor mistakes. Here are two examples for pages with a properly formatted title:

And here are a couple of examples of titles with minor mistakes:

- May 21, 2019—KB4497934 (OS Build OS 17763.529) (an extra “OS”)

- September 29, 2016 — KB3194496 (OS Builds 14393.222) (“Builds”, but just one build)

- January 26, 2017—KB 3216755 (OS Build 14393.726) (the only entry with a space after “KB”)

- July 16, 2019—KB4507465 (OS Build 16299.1296 ) (a space before “)”)

Downloading the updates from the Microsoft Update Catalog

Most updates are available for three architectures: x86, x64 and ARM64. There are also updates for Windows Server in addition to Windows 10, but most, if not all of them are the same files for both Windows 10 and Windows Server. For now, I decided to limit the scope to x64.

This part wasn’t as easy as the previous one, mainly because it’s so time consuming. In addition, it turned out that not all of the updates are available in the Microsoft Update Catalog. Out of the 502 updates available for Windows 10 while writing these lines, only 355 are available for x64. Out of the 147 which aren’t available, 27 are for Windows 10 Mobile (discontinued), one is only for x86, and one is only for Windows Server 2016. The other 118 are truly missing, 2 of which have a “no longer available” notice, and the others’ absence is not explained. Here is a detailed table with all of the updates and their availability for x64.

Querying VirusTotal

There are files of various types in the update packages, including non-PE files such as txt and png. For now, I decided to focus on exe, dll and sys which are the most common PE file types, even though there are other PE file types such as scr.

Querying VirusTotal is quite simple, as I demonstrated with the Python script in the previous section about VirusTotal. The problem was that I needed to query information about 134,515 files, which is not a small amount. I was afraid of a strict rate limiting, but fortunately, the rate limiting wasn’t so strict. After a while I got a response similar to the following:

{

"error": {

"code": "TooManyRequestsError",

"message": "More than 1000 requests from 66.249.66.153 within a hour"

}

}So no more than 1000 requests within an hour, which means 5.5 days of downloading. I could use more computers, but that would be inconvenient. Even though it’s not too bad, I was uncomfortable seeing my script waiting every hour for the next quota of 1000 requests, so I used PyMultitor, the Python Multi Threaded Tor Proxy tool created by Tomer Zait. I heard about the tool a while ago, and finally had the perfect use case for it. I was pleasantly surprised how stable and easy to use it is (stability should also be attributed to the Tor project). With PyMultitor, I was able to reduce the time to 3 days of downloading.

Of course, no data is returned if a file was never submitted to VirusTotal. Out of the 134,515 files, 108,470 were submitted, which is a success rate of 80.6%. Not bad! Also, 190 of the files were submitted, but the report for them didn’t contain details about the PE format. Rescanning them solved the problem.

The result

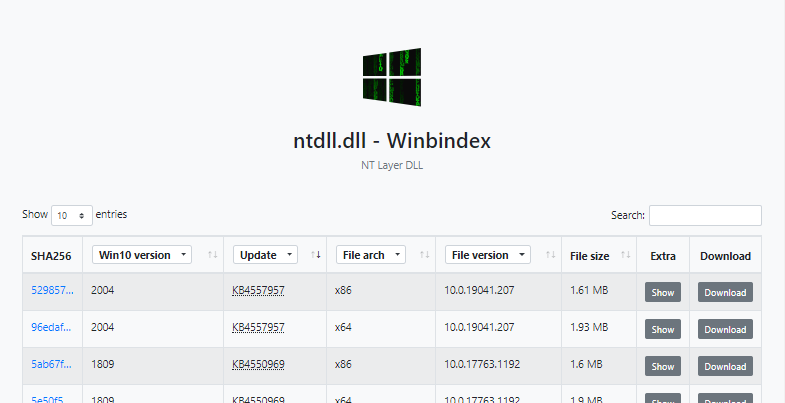

After building the index of files, I created a simple website which displays the data in a table. Here it is: Winbindex - the Windows Binaries Index

All the files that were found in the update packages are listed, but currently only exe, dll and sys files have download links, except for those that weren’t submitted to VirusTotal.

Possible further work

I think that the index can already be very useful, but it’s not complete. Here are some things that can be done to further improve it:

- Indexing files from base builds. Currently, files which don’t appear in any update package, but appear in the initial Windows release aren’t indexed. To fill the gap, I’ll probably have to get the corresponding ISO files of the initial Windows releases.

- Indexing files which aren’t available on VirusTotal. There are several possible options here:

- Automating a VM that updates itself and grabs all the files.

- Understanding the diff algorithm to be able to get all the files from the update packages.

- Using the Unified Update Platform, although I’m not familiar enough with it to say if it can help with this.

- Indexing files of other architectures: x86 and ARM64, and of other Windows versions: Windows 7, Windows 8/8.1.

I don’t plan to do any of that in the near future, but I might do that one day when I stumble upon another task which requires it.