Implementing Global Injection and Hooking in Windows

A couple of weeks ago, Windhawk, the customization marketplace for Windows programs, was released. You can read the announcement for more details and for the motivation behind creating it. In this post, I’ll focus on my journey in implementing the technical aspects of Windhawk. If you prefer reading code to reading text, check out the demo implementation.

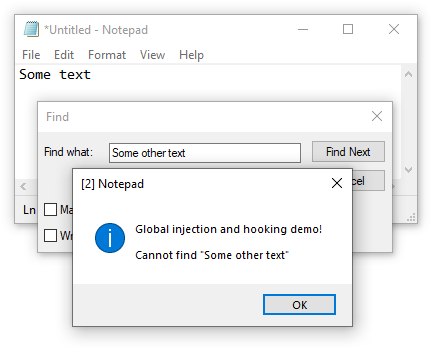

Windhawk allows creating mods, which are C++ snippets that are compiled to DLLs and loaded in third party programs to customize them. The technical challenge is to be able to load these DLLs in the context of the required processes. For example, one can create a mod that hooks the MessageBoxW WinAPI function, and define that the mod should apply to all processes.

Windhawk implements a mod manager which is injected into all processes. Injecting a DLL into all processes is not a novel task, it has been done multiple times before by antiviruses, customization tools, and other programs. To the best of my knowledge, these are the most common approaches:

- Using a kernel driver - A nice proof-of-concept implementation can be found here.

- Using

SetWindowsHookEx- Can be used to install a hook procedure to monitor the system for certain types of events. Only applies to processes that loaduser32.dll. Limited to processes in the same desktop. Has limitations regarding UWP apps. - Using

AppInit_Dlls- A legacy infrastructure that provides an easy way for custom DLLs to be loaded into the address space of every interactive application. Only applies to processes that loaduser32.dll. Starting in Windows 8, theAppInit_DLLsinfrastructure is disabled when secure boot is enabled. - Using esoteric, undocumented hooks - You can see several examples for these in the Hooking Nirvana talk by Alex Ionescu.

These were my goals for the global injection solution:

- Minimal privileges - I wanted Windhawk to be able to run even without administrator rights. And in general, I preferred to avoid installing a driver which is too intrusive to my taste and can affect the system’s stability.

- Minimal intrusiveness - I preferred to avoid modifying system files or registry entries, doing all the work in memory, such that all changes are temporary and there’s no risk of causing permanent damage to the system.

- Minimal limitations - I strived to allow customizing as many programs as possible. For example, I tried to find a solution that is not limited to processes that load

user32.dll, and that has no limitations regarding UWP apps. - Universal solution - I looked for a solution that works on all or most Windows versions, and that is unlikely to stop working in the future.

Also, it’s worth listing some of the non-goals for the solution:

- Stealth - DLL injection is often misused by malware, and one of their goals is staying undetected for as long as possible. To achieve that, malware authors try to find novel injection methods which are not known to security vendors and are not detected by security software. As my project has no malicious intentions, hiding the injection is not necessary. In fact, I preferred a standard solution that is as transparent as possible.

- Security - DLL injection is often used by security software. An antivirus, for example, may decide to intercept all file access and limit access to sensitive files. In this case, it’s important to make sure that the limitation can’t be bypassed. My project has no security implications and doesn’t need to be protected from bypasses.

Looking for the best approach

I started by looking for the approach that fits my goals best. Here’s a table which summarizes my findings (note that those are not yes/no criteria and the table is mostly a judgment call):

| Minimal privileges | Minimal intrusiveness | Minimal limitations | Universal solution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A kernel driver | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

SetWindowsHookEx |

✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

AppInit_Dlls |

❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Esoteric hooks | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ |

Out of the four approaches, the SetWindowsHookEx approach seemed to be the best fit, but it has its limitations which I hoped to avoid. Also, using SetWindowsHookEx felt like a misuse of a tool designed for different purposes as I must choose an event to get notified about, even if I don’t need any.

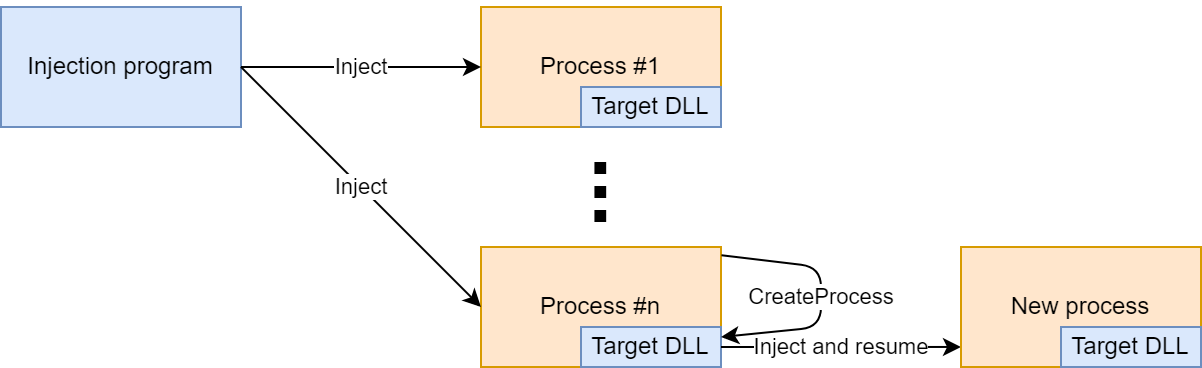

After some thought, I decided to try another approach: Instead of using a dedicated global injection mechanism, implement injection for a single process. Then, use it to implement global injection as following:

- Initially, enumerate all processes and inject into each of them.

- For each of the injected processes, intercept new process creation (e.g. by hooking the

CreateProcessWinAPI function) and inject into each newly created process.

This approach looks rather obvious and simple to implement, but in practice there are various tricky details that have to be taken care of. I’ll go through them in this post. I’m sure this approach was implemented and used before, but I didn’t find a fully working implementation which I could use as a reference.

Injecting a DLL into a process

Typically, process injection follows these steps: Memory allocation, memory writing, code execution. I’ve used the classic and straightforward injection method:

VirtualAllocExfor allocating memory in the target process.WriteProcessMemoryfor writing the code into the allocated memory.CreateRemoteThreadfor creating a new thread in the target process to run the code that was written.

The injected code loads the DLL, achieving the required task.

This injection method is very old and well known, and there are many tutorials and examples for it on the internet, so I won’t elaborate further.

Injecting a DLL into all processes

As mentioned before, the idea is to enumerate all processes and inject the DLL into each of them. To make sure the DLL is also loaded in newly created processes, intercept new process creation and inject into each newly created process.

A simple implementation can be found here. A couple of notes about the implementation:

- When launched as administrator, the program enables debug privilege. This allows injecting the DLL into system services. As a result, this enables injecting the DLL into newly created processes that are launched as administrator, since those processes are in fact created by the

AppInfoservice, and so hooking itsCreateProcessInternalWfunction is required. For details, refer to the blog post Parent Process vs. Creator Process by Pavel Yosifovich. CreateRemoteThreaddoesn’t allow creating a thread in a remote 64-bit process from a 32-bit process. The wow64ext library is used to overcome this limitation.- In Windows 7,

CreateRemoteThreadfails if the target process is in a different session than the calling process. A workaround is to useNtCreateThreadExinstead. - To intercept new process creation,

CreateProcessInternalWis hooked. Looks like all documented process creation functions end up calling it:CreateProcessA→CreateProcessInternalA→CreateProcessInternalWCreateProcessW→CreateProcessInternalWCreateProcessAsUserA→CreateProcessInternalA→CreateProcessInternalWCreateProcessAsUserW→CreateProcessInternalW

- The MinHook library is used for hooking the

CreateProcessInternalW,MessageBoxWfunctions. - After being injected, the DLL waits for an event to be signaled, then unloads itself.

- Refer to the repository’s README file for compiling and running instructions.

At first glance, it seemed to be working nicely and looked pretty much complete. But upon a closer inspection and after some careful testing, I found that there are several limitations that have to be addressed.

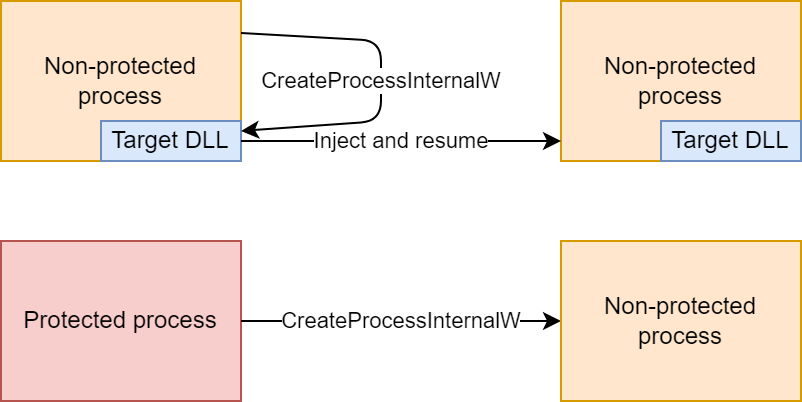

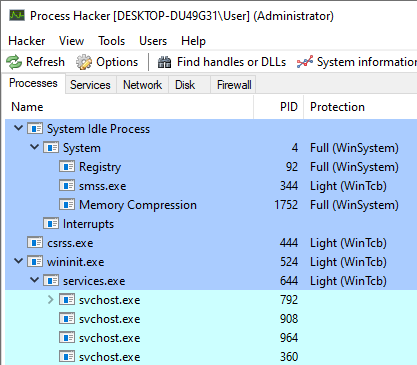

Inaccessible processes and broken injection chains

Even when the injection program is running as administrator, and even when debug privilege is enabled, there are processes which are out of reach. Several core system processes in Windows are marked as Protected Processes, and as the name implies, they’re protected from tampering and the injection program can’t inject the DLL into them. That’s not a problem by itself, these processes are protected for a reason and I’m OK with not being able to fiddle with them. The real problem is that because they’re protected, CreateProcessInternalW is not hooked and there’s no opportunity to inject the DLL into processes created by protected processes, even if the created processes are not themselves protected.

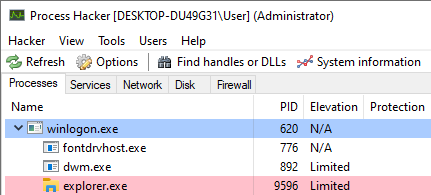

For example, you can see on the screenshot below that services.exe is a protected process. As a result, the DLL won’t be injected into child svchost.exe processes which are launched after the injection program. svchost.exe processes which were already running are handled by the process enumeration.

A similar problem exists when the injection program is not running as administrator - it can’t inject the DLL into elevated processes, which is a security limitation and that’s OK, but it also loses the opportunity to inject into unelevated processes created by elevated processes.

For example, in the screenshot below Windows Explorer was restarted via the Task Manager. The new explorer.exe process was created by winlogon.exe, which is elevated.

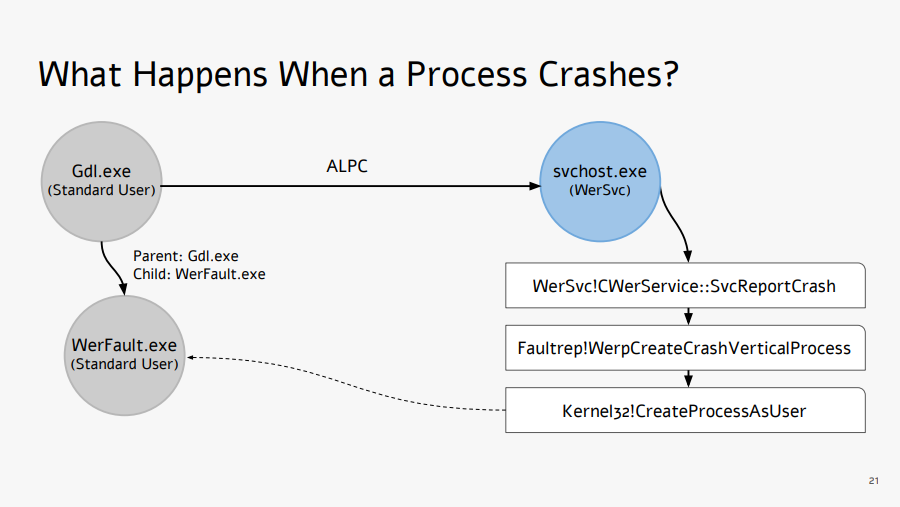

Another common example where an elevated process creates an unelevated process is when a process crashes. See the screenshot below from the presentation Exploiting Errors in Windows Error Reporting by Gal De Leon. In this case, the injection program misses the opportunity to inject the DLL into WerFault.exe which is unelevated. WerFault.exe may in turn restart the crashed program, and it will be missed as well.

The solution that I came up with is to make the injection program monitor for new process creation, and for each newly created process, try to inject into it from the injection program.

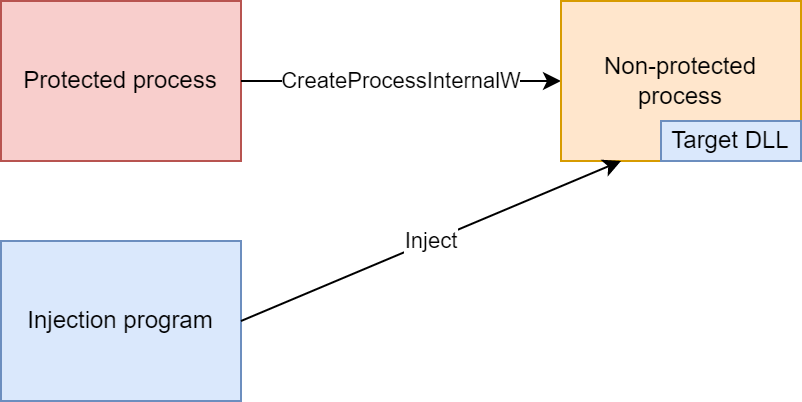

If the new process was created by an inaccessible process, the injection program injects the DLL, as depicted below.

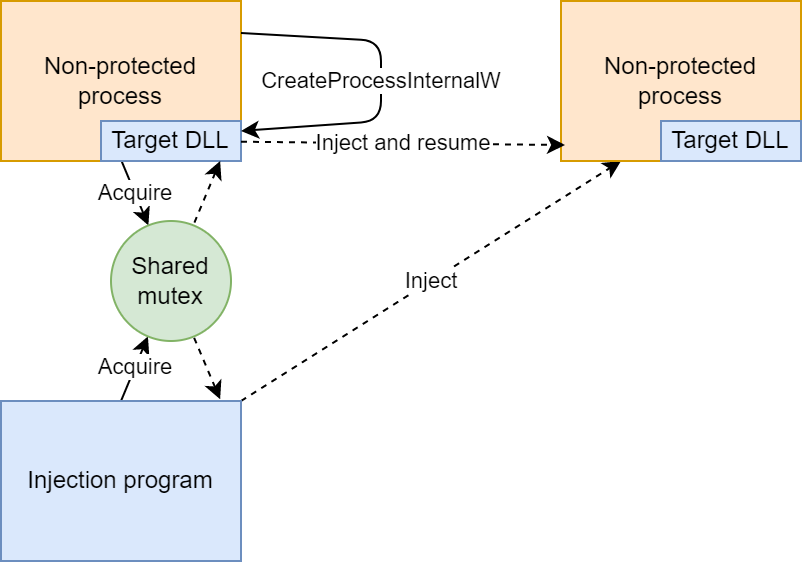

If, on the other hand, the new process was created by a process with an injected DLL, there’s a race between the creating process and the injection program. I used a mutex to make sure only one of them injects the DLL, as depicted below.

This approach works, but it has a serious drawback - if the new process is created by an inaccessible process, the DLL is injected asynchronously, possibly after the new process begins running, which might be too late depending on the customization use case. Unfortunately, I didn’t find a better solution, and because this problem is not very common (especially if the injection program is running as administrator), it’s not too bad.

Also, this solution created a new problem which is described below, which was happening when the injection program injected the DLL too early.

Too early injections that break stuff

After implementing the solution above, I noticed that sometimes, new processes failed to start. After a bit of investigation, I saw that it only happened with console programs. And after more investigation, I found the root cause.

All user mode threads begin their execution in the LdrInitializeThunk function. The first thread that a process runs performs process initialization tasks before the execution is transferred to the user-supplied thread entry point. One of the process initialization tasks is creating the console window in case the process is a console process. For more details about the LdrInitializeThunk function, check out this blog post by Ken Johnson.

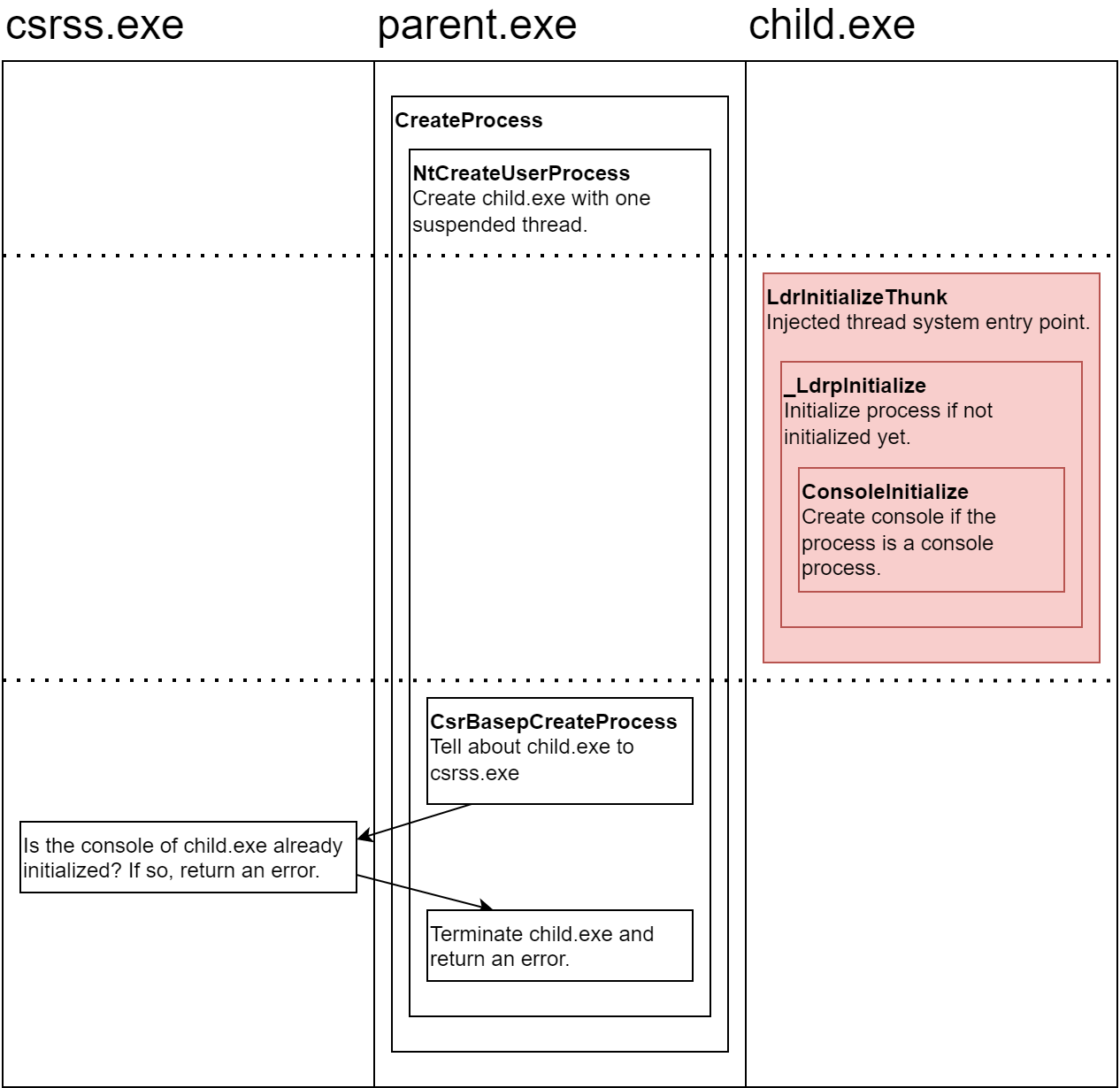

Normally, a new process starts with a single, suspended thread. Then, the Client/Server Runtime Subsystem (csrss.exe) gets notified about the new process that was just created, and does its own handling. Finally, the suspended thread is resumed, the LdrInitializeThunk function performs process initialization tasks and transfers the execution to the process entry point.

With the injection program injecting the DLL too early, the new process starts with a single, suspended thread, as usual. But before the Client/Server Runtime Subsystem (csrss.exe) gets notified about it, the injection program creates a new thread in the new process which starts executing right away (marked with red in the image below). As the first running thread, it performs the process initialization tasks. Only then, csrss.exe gets notified about the new process, but it doesn’t expect the process to have an initialized console, and returns an error.

To overcome this and other potential problems caused by the early injected thread execution, I switched from creating a new thread with CreateRemoteThread to queuing an APC (Asynchronous Procedure Call) in cases when the process didn’t start executing yet. For a great technical blog post about APCs check out APC Series: User APC API by Ori Damari. A couple of notes about the implementation:

- The undocumented

NtQueueApcThreadfunction is used, since the documentedQueueUserAPCfunction is not suited for inter-process APC queuing because of the activation context handling. NtQueueApcThreaddoesn’t allow queuing an APC in a remote 64-bit process from a 32-bit process. The wow64ext library is used to overcome this limitation.- For queuing an APC in a remote 32-bit process from a 64-bit process, the address parameter has to be encoded. I used the APC Series: KiUserApcDispatcher and Wow64 blog post by Ori Damari as a reference.

But how does the injection program know whether the process started executing (and then CreateRemoteThread is used as before) or not (and then an APC is queued)? It checks whether there’s only a single thread, and if so, whether it’s suspended with the instruction pointer at RtlUserThreadStart. In that case it concludes that the process didn’t start executing and queues an APC instead of creating a remote thread.

Supporting UWP apps

The next thing I noticed is that the DLL wasn’t getting injected into processes of UWP apps such as Windows Calculator. The code to load the DLL was being injected successfully, but the DLL failed to load with ERROR_ACCESS_DENIED. The problem was that UWP apps have limited access to the filesystem and they didn’t have permissions to load the DLL. Changing the DLL file permissions fixed this issue. For example, the following commands can be used to change the DLL file permissions such that UWP apps are able to load it:

icacls global-inject-lib.dll /grant everyone:RX

icacls global-inject-lib.dll /grant *S-1-15-2-1:RX

icacls global-inject-lib.dll /grant *S-1-15-2-2:RX

Another problem was that a mutex can’t be shared between the injection program and UWP apps by using the same mutex name. UWP apps are sandboxed, and each UWP app has its own object directory. A UWP app can’t refer to objects outside of its object directory by name. I was able to overcome this limitation by using the little-known private namespaces API. For a great overview of named objects in Windows, including the UWP sandboxing and private namespaces, check out the blog post A Brief History of BaseNamedObjects on Windows NT by James Forshaw.

Process mitigation policy and system errors

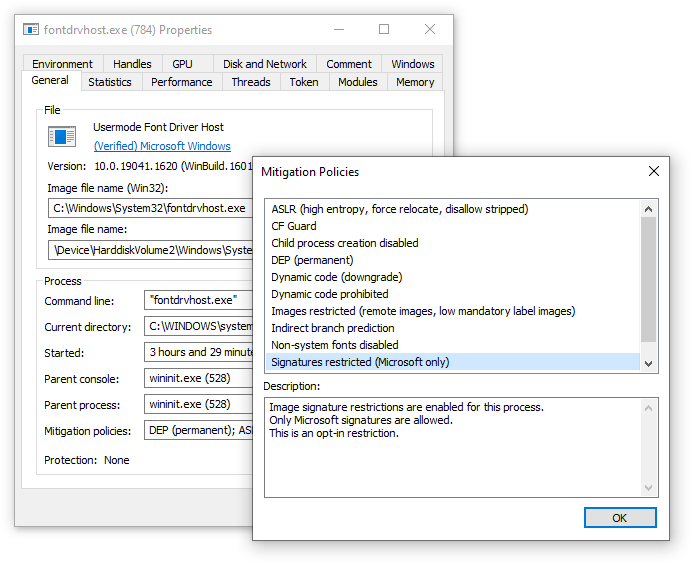

Another case in which the DLL wasn’t getting injected into processes was for processes with a mitigation policy that restricts image loading to images that are signed. On my test Windows 10 machine there were two such processes: fontdrvhost.exe and svchost.exe which hosts the DiagTrack service (diagtrack.dll).

Similarly to the UWP case, the code to load the DLL was being injected successfully, but the DLL failed to load, this time with ERROR_INVALID_IMAGE_HASH. But unlike the UWP case, there’s no straightforward workaround. I could try and use reflective DLL injection (manually loading the DLL from memory), but I didn’t bother since it complicates the solution and might have pitfalls for the little benefit of being able to customize programs which are not very interesting anyway.

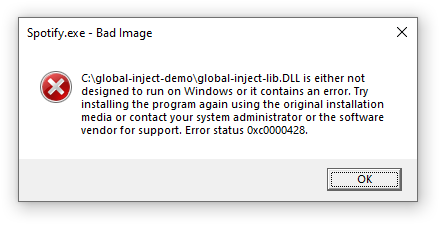

I was OK with not being able to customize programs with this mitigation, but this limitation had an unpleasant side effect. In some cases, Windows was displaying a system error when the DLL loading failed:

The system error can be reproduced by running the following program and then running the injection program:

#include <windows.h>

int WINAPI WinMain(

HINSTANCE hInstance,

HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

LPSTR lpCmdLine,

int nShowCmd

)

{

PROCESS_MITIGATION_BINARY_SIGNATURE_POLICY p = { 0 };

p.MicrosoftSignedOnly = 1;

if (SetProcessMitigationPolicy(ProcessSignaturePolicy, &p, sizeof(p))) {

MessageBox(NULL, L"Mitigation applied, press OK to exit", L"", MB_OK);

}

}

After some investigation, I found that this behavior can be controlled with the SetErrorMode, SetThreadErrorMode WinAPI functions. I used SetThreadErrorMode to turn off the critical-error-handler message box while trying to load the DLL.

Hooking performance

After handling all of the limitations above, the solution felt pretty solid and I didn’t encounter any other problems. But after using the computer with it for a while, I noticed that it takes noticeably longer for some programs to launch. The reason for this was that MinHook, the hooking library that I used, enumerates all the threads on the system and looks for threads that belong to the current process to suspend them. Enumerating all system threads can be very slow, on my system it took more than 300 milliseconds. I improved this by doing the following:

- Instead of enumerating all threads on the system, I use the undocumented

NtGetNextThreadfunction to directly enumerate threads that belong to the current process. In addition to improving performance, it also improves stability by avoiding race conditions. For a comprehensive overview, check out the Suspending Techniques research by diversenok. - When injecting into a process which didn’t start executing yet, I skip the thread enumeration altogether, since there should be no other running threads anyway.

You can find the code that enables this in my MinHook multihook branch. Among other changes the branch has is the ability for a function to be hooked more than once. In general, I found that reliable function hooking is more tricky than it might seem at first. For example, consider what happens if a DLL sets a hook and then needs to be unloaded. When is it safe to unload it? Can you be sure? But that’s a topic for another post.

Implementation code and summary

An implementation that handles all the limitations mentioned in this post can be found here. I’m pretty satisfied with the result. I’ve been using my computer with Windhawk, which uses this global injection and hooking implementation, for several months, and I didn’t experience any stability, performance, or any other problems. I hope that Windhawk will prove itself as a reliable tool for customizing Windows programs, and I invite you to try it out.